Social Web in the Wild

Introduction

The previous chapter discusses an individual's relation with their online representation; how users understand profiles; how the affordances of a profile impact the culture of an online community, including how users interact and relate to each other, and how users understand themselves as part of the community. This chapter contains original studies; two which examine online profiles from an outside perspective, by looking at what systems offer and how individuals appear to be making use of this. Three of the studies go behind the scenes to actually ask profile owners about their participation in the social Web ecosystem.

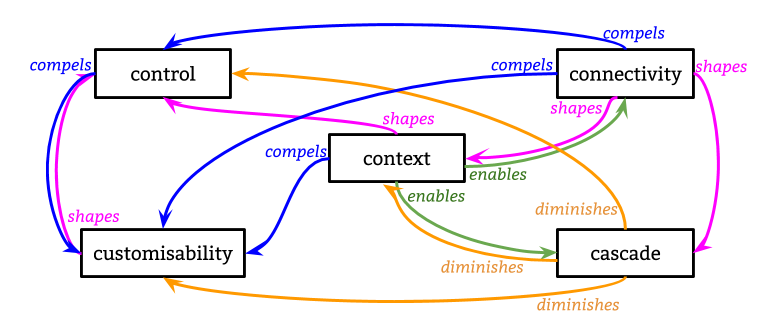

Each study resulted in a small taxonomy useful for categorising the participants' experiences in each particular scenario. A core contribution of this thesis is to coalesce the results of these new studies, along with knowledge from existing literature, into an overall framework consisting of five concepts. This framework - the 5 Cs of Digital Personhood - constitutes the key components for describing online self-expression experiences. The framework is summarised here for reference, and I discuss its derivation in more detail in the conclusion of this chapter.

Each component encapsulates a variety of different parts or aspects which are revealed through the studies in this chapter, as well as prior research:

- Control: over persistence or ephmerality of identities, attachment or not to real names, traceability between different identities (eg. Can I delete my profile?).

- Customisability: of the data that is included in an online representation, the extent to which this is available to others, and how it is presented (eg. Can I change the name that appears on my profile?).

- Connectivity: to others and an audience, known or imagined, and how impressions by this audience can be managed (eg. Do I know how this profile appears to my mother?).

- Context: the social/cultural expectations of a platform or community; personal motivations and use cases; technical constraints of systems; offline cultural norms or biases which affect or constrain online behaviours (eg. Are the people who control this platform obliged to adhere to the same laws as I am?).

- Cascade: of personal information throughout a network, perhaps unknown; 'profiles' generated by algorithms, data passed around by third parties or collected through surveillance; expression 'given off' over which individuals have little knowledge or control (eg. Is my data being used to recommend products to me?).

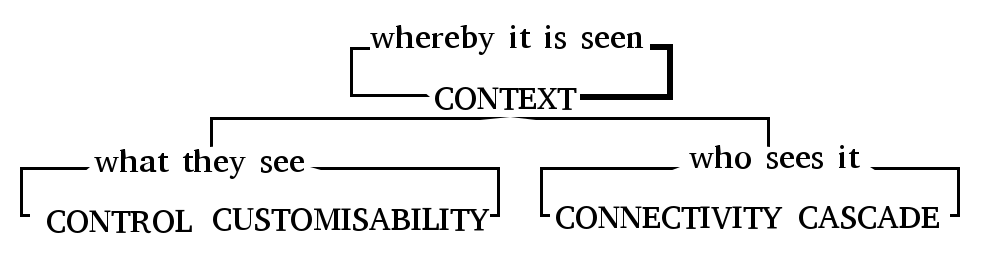

Whilst all five components influence each other in complex and shifting ways, I illustrate key relations with the following terms:

- compels: the existence of aspects of one necessitates the involvement of aspects of the other.

- diminishes: aspects of one reduce the effect of aspects of the other.

- enables: aspects of one increase the effect of aspects of the other.

- shapes: aspects of one feed into aspects of the other; the latter is formed according to or depending on variations in the former.

Overview of studies

Table 1 summarises the methods, inputs and outputs of the five studies in this chapter.

The previous chapter established that there are various different (potentially overlapping) perspectives that need to be taken into account when discussing online self-presentation:

- Active users of a system, who maintain a profile.

- Passive users of a system, who may not have a profile of their own.

- System designers and developers, who must model and display data about their users.

- Third-party developers who build additional services using data from another system.

- Outside bodies which seek to influence or direct how systems are used for legal, ethical or economic reasons.

The five empirical studies in this chapter touch on each of these perspectives to some degree.

The first study sets a baseline for describing and categorising online profiles by asking the question "what is a profile?" and takes an objective look at 18 online systems which employ user profiles in a social capacity to classify their features. Subsequent studies focus on the people behind the profiles, or behind the systems themselves.

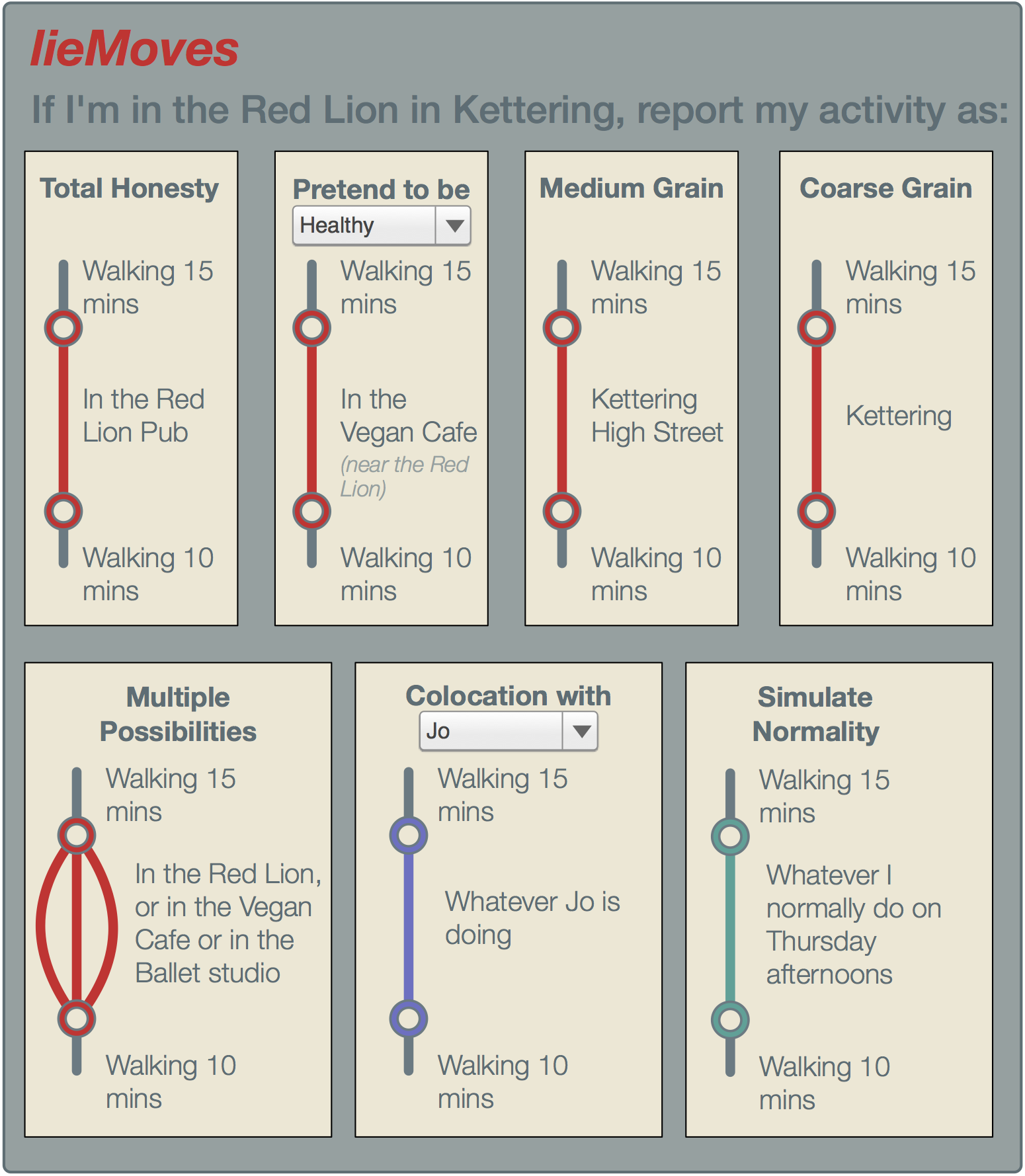

As hinted at in the previous chapter, individuals are rapidly and often intuitively developing coping mechanisms and practices to improve their handling of online self-presentation and impression management despite the constraints of the tools they use. The studies build on this background, first by observing system users from the outside (in the case of creative content producers on YouTube), and then by asking them questions and exploring their feelings and experiences with online profiles, with regards to: deception and lying on social media; imagining social systems as tools for mediating reality; and designing and building one's own customised social systems.

| Study | Type | Participants | Publication | Perspectives | Resulting terminology/themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What is a profile? | Descriptive, observational | 18 | n/a | A S T | flexibility, access control, prominence, representation, portability |

| Constructing online identity | Empirical, observational | 10 | WWW14 | A | roles, attribution, accountability, traceability |

| The many dimensions of lying online | Survey | 500 | WebSci15 | A P S | system, authenticity, audience, safety, play, convenience |

| Computationally mediated pro-social deception | Interviews, design fictions | 15 | CHI16 | A P O | effort & complexity, strategies/channels, privacy & control, authenticity & personas, access & audience, social signalling & empowerment, ethics & morality |

| #ownYourData | Interviews | 15 | n/a | A S T O | self-expression, persistence/ephemerality, networks & audience, authority, consent |

| Perspectives: | A — Active users; P — Passive users; S — System developers; T — Third party developers; O — Outside bodies | ||||

| Publications: | WWW14: | Guy A. & Klein E. (2014) Constructed Identity and Social Machines: A Case Study in Creative Media Production. Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference Companion on World Wide Web - WWW'14 Companion. | |||

| WebSci15: | Van Kleek, M., Murray-Rust D., Guy A., Smith D., O'Hara K., & Shadbolt N. (2015). Self Curation, Social Partitioning, Escaping from Prejudice and Harassment: The Many Dimensions of Lying Online. Proceedings of the ACM Web Science Conference. 10:1-10:9. | ||||

| CHI16: | Van Kleek, M., Murray-Rust D., Guy A., O'Hara K., & Shadbolt N. (2016). Computationally Mediated Pro-Social Deception. Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 552–563. | ||||

What is a profile?

This is a descriptive study of 18 systems which employ profiles in a social capacity. This study results in five features and each system is scored according to the degree each feature is present. Using these features we can cluster similar systems together, or differentiate them, and future studies can use these features to create baseline descriptions or characterisations of systems for comparison. The features are: flexibility, access control, prominence, portability, representation.

Introduction

In order to build on our understanding of the role an online profile plays in self-presentation, identity and interaction we need a more nuanced understanding of what a ‘profile’ is in a general sense. What is the meaning of profile? I carried out an empirical analysis of digital representations of users of 18 different online systems. From this analysis I derive a set of constructs to capture features of profiles in online systems. I propose this for assessing the benefits and drawbacks of how profiles are implemented in existing systems in such a way that takes into account the scenarios in which they are used, as well as groundwork for deriving requirements for profiles when designing new systems which need digital representations of their users. Once we have a characterisation of a particular type of profile a system enables, we can use these as control features when comparing systems side by side. Interesting future study would be to determine how the features of a profile influence actions of users or community formation, and vice versa.

For the purposes of this thesis, I define social systems to be Web-based networked publics which offer individuals consistent and reusable access to an account which they can personalise and use to interact in some form with others in the system.

Context and research questions

Profile generation is an explicit act of writing oneself into being in a digital environment (boyd, 2006 [boyd06])

boyd's definition of profile generation above is based on teenagers' use of Friendster and MySpace in 2006. Today, online social systems use profiles in a variety of different ways, and present them in a variety of configurations. Profile generation is not only explicit, but can occur implicitly, without necessarily even the consent or awareness of the profile subject. As discussed in the previous chapter, studies of online profiles tend to focus on oversimplifications or very specific (unrealistic) use cases, which do not take into account the broader system in which the profile exists. This approach often reduces an individual's representation in the system to a single document or webpage, and neglects the rich array of interactions and activities in which they engage in order to create a presence for themselves. In reality, profiles vary in how they are constructed and the roles they play.

This study serves to introduce a formal classification of profile features, and asks the following questions:

- What are common features of the ways users are represented in online social systems?

- How do these features vary between systems?

Kaplan & Haenlein (2010) categorise social systems into six groups [kaplan10]:

- Blogs are "special types of websites that usually display date-stamped entries in reverse chronological order"

- Social Networking Sites are "applications that enable users to connect by creating personal information profiles, inviting friends and colleagues to have access to those profiles, and sending ... messages between each other"

- Collaborative Projects "enable the joint and simultaneous creation of content by many end-users"

- Content Communities are for "the sharing of media content between users"

- Virtual Gaming Worlds are "platforms that replicate a three-dimensional environment in which users can appear in the form of personalized avatars and interact with each other ... according to strict rules in the context of a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG)"

- Virtual Social Worlds "allows inhabitants to choose their behavior more freely ... there are no rules restricting the range of possible interactions"

The subjects of this study (see Table 2) are a cross section of these, but there are also some which do not fit into this framework. Since Kaplan & Haenlein's categorisation, (at least) two new types of system have emerged:

- Quantified Self: life-logging or self-tracking; automated or manual recording of minutiae of daily life;

- Transactional: networks that exist for exchange of goods or services.

Study Design

This is a descriptive study [#], which aims to gather and present information about the current state of social systems with regard to how their users are represented. I do not try to determine causal effects between features of systems, nor do I hypothesise about how these features impact users. Rather, I provide a characterisation of a set of systems as a foundation for future exploratory research.

Method

I started with the following areas to investigate:

- Data contained within a profile.

- How profile data may be accessed by others (within and outside of the originating system).

- How profile data may be distributed or pushed to others (within and outside of the originating system).

- The role of profile data within the broader system.

The starting point for a 'profile' was typically a unique identifier for an entity (which could be an individual or group) such as a URL or username. After initial explorations of the profiles in a few systems, these areas were refined into specific questions:

- What does a profile contain?

- How are profiles within a system connected together?

- How are profiles updated?

- How are people notified when a profile is updated?

- How is access to a profile controlled?

- How can profiles be exported from or imported into a system?

- What constraints are placed on a profile?

- How do profiles fit in with a systems apparent data model?

- What is the profile for?

- Who is the profile for?

I took one system at a time, and answered all of the questions by logging in (where applicable) to my own account and observing the behaviours of the system in response to interactions with my own and other users' profiles (where necessary), and took screenshots. I also read systems' terms of service, "About" pages, introductory descriptions or statements of purpose, and leaned on my own background knowledge of how the systems are used by myself and others.

Having answered all of the questions about each system, I passed through each one again to confirm, and add more detail if necessary, and I noted similarities and differences between systems. From the results, I derived a set of potential features for profiles, and ranked each system according to the presence of features. This allowed some clustering of similar systems into a general categorisation framework.

Subjects

18 social systems were selected for the initial analysis phase. Most are ordinary websites which one uses by registering, then logging in and out. Some include or require self-hosted software.

Popular systems which I have personal experience were chosen, in order to take advantage of latent background knowledge when navigating the systems.

The information in Table 2 serves to give a feel for the diversity of the social systems being studied.

| System | URL | Type | Specialisation | Overview | Categoryk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AirBnb | airbnb.com | website | travelers | Accommodation renting | T | |

| CouchSurfing | couchsurfing.com | website | travelers | Accommodation, cultural exchange, new connections | T | |

| facebook.com | website | general | New and existing connections | SNS | ||

| Friendica | friendi.ca | website / software | general | New and existing connections | SNS | |

| Github | github.com | website | developers | Collaborate on software | CP | |

| Indieweb wiki | indieweb.org | website | developers | Collaborate on ways to develop social web presence | B, CP | |

| linkedin.com | website | professional | New and existing connections | SNS | ||

| OkCupid | okcupid.com | website | relationships | New connections | SNS | |

| PeoplePerHour | peopleperhour.com | website | professional | Hiring freelancers | T | |

| Pump.io | pump.io | website / software | general | New and existing connections | SNS | |

| Quora | quora.com | website | general | Q&A (any topic) | CC | |

| ResearchGate | researchgate.net | website | academic | Advertise/find research publications | CC | |

| RunKeeper | runkeeper.com | website | sports | Track sporting activities | QS, CC | |

| StackOverflow | stackoverflow.com | website | developers | Q&A (tech) | CC | |

| Tumblr | tumblr.com | website | general | New and existing connections | CC, SNS, B | |

| twitter.com | website | general | New and existing connections | B, SNS, CC | ||

| YouTube | youtube.com | website | general | Consume/create media | CC | |

| Zooniverse | zooniverse.org | website | science | Citizen science | CP | |

| Categories from Kaplan & Haenlein: B — Blog (including Microblog); SNS — Social Networking Site; CP — Collaborative Project; CC — Content Communities | ||||||

| Additional: QS — Quantified Self; T — Transactional | ||||||

Limitations

As with everything in this thesis, this study is limited by a Western, English-speaking perspective on the systems in question. The observations were conducted from an IP address in either the UK or the US, and I did not attempt to find out how each system differs based on the language preferences or geographical location of users.

Significantly these systems change over time, often rapidly, in response to changing markets, legislation, and available technologies. Most of the data was collected and screenshots captured in the summer of 2015. Some data points were verified to be largely in line with the original findings, but not deeply verified, during writeup in spring 2017. It is important to note that the results are a dated snapshot which cannot be assumed to hold true indefinitely.

I will emphasise again that the nature of a descriptive study does not give any indication of cause-effect relationships between any of the results. Similarly, I can only describe systems as they appear, and not speculate as to why they appear such.

Results

Here I summarise the findings of the study.

The most distinct of the systems is the Indieweb wiki, which largely functions as an ordinary wiki except that one identifies oneself with a domain name (logging in with the IndieAuth authentication protocol) and thus the 'profile' is tied to one's personal blog, website, or homepage. As a result, profiles are highly custom and diverse; even though they are not hosted centrally by the wiki software they are the main source of identification between users of the wiki, so they are considered here in the same way as the profiles in other systems. In order to study them without visiting the domains of every single user, I also make use of the contents of the wiki itself, which is focused around documenting and recommending best practices for creating a social Web presence; that is, I assume that practices relevant to profile creation described the wiki are adopted by a majority of users.

What does a profile contain?

Profiles contain some combination of: attributes (key-value pairs of data); content (text or media) created by the profile owner; a list of activities or interactions the profile owner has carried out in the system; links to profiles with which they are connected; links to content the profile owner has interacted with (e.g. 'likes'); links to collections of content curated by the profile owner; statistics about the profile (e.g. 'member since'); automatically generated rankings or ratings of the profile owner; reviews, messages or content left by other members of the network.

All of the 18 systems use attributes in the profile, and none use only attributes. Attributes may be generic (such as name, bio, location), as well as tailored to the specific system (countries I've visited on CouchSurfing; knows about on Quora; looking for on OkCupid). Some attribute values are offered as a fixed set to choose from, and others permit free-text input. Some systems may require a minimum input of certain attributes, and some leave everything entirely optional.

Facebook has the broadest array of possible attributes, including the possibility to create your own keys, and use ones that others have created. CouchSurfing and OkCupid make extensive use of free text input, prompting users to write short essay-style answers to certain questions. Most systems encourage an avatar or display picture, and several also permit uploading a prominent header image (also known as 'banner' or 'cover photo'). The Indieweb community bases attribute-style profile content around the microformats h-card specifications, which provides a fixed set, all optional.

Indieweb profiles tend to be the homepages of blogs (although they may be a more static 'about' page) and are heavy on the content and activities aspects. SNS like Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pump.io and Friendica, also lend prominence to content (typically text-based status updates; often photos) and a feed of activities on the site. YouTube incorporates videos created by the profile owner, and how these are organised is highly customisable. For users who have not uploaded video, YouTube profiles contain mostly attributes and activities, and elevate interactions with other content on the site, such as commenting on videos, adding to playlists, and subscribing to channels.

Activity feeds in general vary in their level of detail. Quora displays if someone edited a question or answer. Pump.io distinguishes between 'major' and 'minor' activities, displaying them in separate feeds. Mixed in with posts by the profile owner, Twitter includes a heavily algorithmically curated subset of activities, such as recent follows or likes. Most sites do not include a complete log of all of the possible interactions however. For example, CouchSurfing enables a rich array of activities, from offering to host a guest, to posting in group forums and arranging events; but none of these are displayed on a user's profile. Similarly, most systems do not display a feed of changes to attributes of the profile, which could also be considered activities.

On the other hand, when users interact with content on a system, for example by liking or favouriting it or adding it to a collection (a playlist on YouTube), reblogging it on Tumblr, voting on it on Quora or StackOverflow; this content becomes part of the profile.

StackOverflow, GitHub, PeoplePerHour, ResearchGate, Quora and RunKeeper are very statistics-oriented. RunKeeper focusses on a feed of offline activities, calculating for example how many calories you lost this week from logged exercise, or how far you ran. GitHub visualises code commits and 'contributions' (helpful interactions with projects) in a coloured grid. ResearchGate and Quora display statistics about how much others have interacted with the profile owner's content. OkCupid also generates statistics based on answers to short, multiple-choice personal questions, and these statistics are dependent on who is viewing the profile, e.g. percentage romantic match, and things like '30% more social'.

Sites which make heavy use of content left by others on a profile are CouchSurfing, AirBnB, and PeoplePerHour. Each of these display reviews of the profile owner by other users, typically in a way that cannot be amended or removed. Facebook allows one to 'write on the wall' of another profile, but users can disable this. However, comments and likes by other users commonly show up alongside activities or created content on a profile as well. LinkedIn prompts users to 'endorse' one another for particular skills, and these endorsements are prominent on profiles. StackOverflow and Quora aggregate ratings left by others on content into overall numbers or rankings to display on profiles.

Many systems give prominence to the connections with other users in the system; LinkedIn displays neither likes nor status updates on the profile, but emphasises contacts and the network around them; Twitter displays followers and following; YouTube, ResearchGate, Pump.io, Friendica, and Quora display subscriptions and subscribers.

How are profiles within a system connected together?

Connections between profiles may be uni- or bi-directional; some systems permit both. Bi-directional connections need to be mutual; triggered by one user and confirmed by the second. Uni-directional connections may or may not need approval from the second user, depending on either the system as a whole or individual user preferences. Some systems contain more than one kind of uni-directional connection, which may be named or displayed differently, and carry different connotations. Systems vary in whether or not they notify other users (than the ones involved in the connection) about new connections.

Systems with uni-directional connections are Twitter, Tumblr, Pump.io, Facebook, Quora, LinkedIn, ResearchGate, Friendca and GitHub ('follow'), YouTube ('subscribe'), OkCupid, PeoplePerHour ('like/bookmark/favourite'). Systems with bi-directional connections are CouchSurfing, Facbook, Friendica, and RunKeeper ('friends'), LinkedIn ('connect'). The intersection of these (systems with both) is Facebook, LinkedIn, and Friendica.

Some Indieweb profiles include a list of others the profile owner follows using XFN markup [xfn], but this is not necessarily widespread. StackOverflow, Zooniverse and AirBnb do not have a means of creating persistent connections between profiles, besides leaving references in the case of AirBnb.

Systems which permit more specific information or categorisation of connections are CouchSurfing (specify 'hosted', 'surfed', 'traveled with' or 'never met' as well as the closeness of the relationship), and Facebook (can specify specific relationships, e.g. 'brother'). When a follow request is sent on Friendica, the recipient can accept it as uni-directional (the follower is labelled a 'fan/admirer') or bi-directional, so the recipient also sees the follower's updates. Bi-directional connections on LinkedIn require a reason or more information as 'proof' of a mutual connection, before the request is even sent.

YouTube connects profiles together through subscriptions to channels, however it also explicitly provides input for profile owners to link to other profiles without creating a subscriber relationship. This lets content creators list, for example, other users they admire, or the people they collaborate with. Many YouTubers use this feature to link to other profiles they have on the site. The system gives users free text fields to name this list, as well as each individual link in the list. This particular phenomenon is examined in more detail in the next study, Constructing Online Identity.

OkCupid connections are uni-directional, and only revealed to the recipient if and when a mutual action is made. On Twitter, following another user sometimes (not consistently) appears as an activity in your timeline; notifications are also sometimes sent to your followers to advertise the new connection.

How are profiles updated?

Profiles may be updated by profile owners via a system's user interface, programmatically through an API (Application Programming Interface; the means through which data can be read or written by third-party software). The latter is relevant because programmatic access suggests that third-party applications (outside of direct control the system itself) can also influence a profile owner's view on the possibilities of the profile.

Most systems provide a Web form to add or update attributes, or a similar UI in a native mobile application. The editing interface and the profile display may be tightly coupled (Twitter, Quora, LinkedIn, ResearchGate) completely divorced, or a combination (Facebook, OkCupid). Indieweb profiles are updated with custom editing interfaces, or simply by editing static HTML; there are currently no specific recommendations for protocols or UIs to edit profile attributes.

For the non-attribute data which makes up a profile, separate, often specialised interfaces for both Web and mobile exist, e.g. for posting status updates or media content. For data like statistics and activities, this content is generated by algorithms or sensors, with no explicit input from the profile owner. In a few cases it may be hidden by the profile owner, but rarely changed. An exception is RunKeeper, where one can edit an automatically generated GPS trace after the fact, which can correct distance and speed records. On CouchSurfing, AirBnB and PeoplePerHour, one may respond to a review left by someone else, but not remove it.

Only Pump.io, RunKeeper and GitHub provide APIs to update all attributes of a profile. Facebook and Zooniverse provide limited update access to certain attributes. Most systems provide write APIs to create, follow and like (or equivalent) non-attribute content.

How are people notified when a profile is updated?

The attention a system draws to profile updates could affect how people engage with their own profiles. When profile attributes are updated by the profile owner, most systems do not notify other users of the system at all.

Facebook however pushes updates to friends' timelines along with status updates and content interactions, though the extent to which it does this for each friend depends on their arbitrary content distribution algorithm, and from a user perspective is hard to predict. The most reliably seen attribute updates are changes to profile pictures, cover photos, and relationship status. Whenever the profile owner updates an attribute on Facebook, they are asked to make it a 'story', which sustains a reference to the fact the attribute changed. Friendica notifies about changes to profile pictures only.

OkCupid and LinkedIn provide the option to enable sharing of changes to profile attributes. In the case of LinkedIn, updates are pushed to contacts' feeds, but may also be displayed to non-immediate contacts in the network as a form of promoting connections. OkCupid may display updates to other users in their activity feeds according to whether the system thinks these people might be interested in your profile. How either of these are decided is opaque to the user.

How is access to a profile controlled?

Systems may provide all-or-nothing access to profiles, make everything public but all optional, provide access control on the basis of groups or networks, or individual users, and provide granular access to individual aspects of profiles.

Systems which have limited or no access control, but make all or most data optional to enter include OkCupid, Quora, CouchSurfing, AirBnB, Friendica, Zooniverse, Pump.io and GitHub. OkCupid and CouchSurfing allow profile visibility to be restricted to other logged-in users. CouchSurfing permits users to hide their full name, and GitHub permits users to hide their email address.

Quora permits users to answer or ask questions as 'anonymous' whilst logged into their account. These questions/answers do not show up on the user's profile. Otherwise, the only other control profile owners have is disabling their online presence. Friendica permits connections to be hidden, as well as certain aspects of content. On AirBnB, profile attributes are optional but hosts can automatically decline users who omit certain attributes.

Systems with more granular concepts of audience than public/private include Pump.io, LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, and ResearchGate. In Pump.io individual objects can be 'addressed' so that only particular groups (which can be created by the profile owner) or individuals can see them. LinkedIn permits visibility of some individual profile attributes to 'everyone', 'my network' and 'my connections'. The profile can be set to publicly visible, with certain attributes individually excluded. Connections can be private or public, and content and interactions can be designated different levels of visibility from entirely private to entirely public, with 'network' and 'connections' in between. ResearchGate enables hiding certain statistics, certain attributes, and certain content. Uploaded papers can be visible to 'everyone', 'mutual followers' or 'ResearchGate members'.

Twitter allows users to 'protect' their profiles, which means only those requesting access can see content and connections; however, all attributes are visible to anyone regardless. Profile owners can block other users, preventing them from seeing everything but their name, display picture and profile banner.

Systems with granular access control across several different aspects of the profile include YouTube, Facebook, RunKeeper and ResearchGate. YouTube provides granular access controls for various attributes, interactions, links to content, some statistics (like number of subscriptions) and content. RunKeeper attributes can be assigned levels of visibility individually ('everyone', 'friends', 'just me').

Facebook has complex granular access controls, including individual attributes, content, interactions, connections and links. Defaults can be set, as well as updated on a per-object basis at the time of posting/creating. Content can be restricted to include or exclude individuals, groups, particular networks. Read and write access controls are distinct; that is, one can create a post that is publicly readable, but comments on that post may be restricted or disabled completely.

Tumblr's use of 'primary' and 'secondary' blogs is interesting; where a blog constitutes a profile, users can essentially have as many profiles as they want attached to one login. Primary blogs (one per login) are always public, but secondary blogs (unlimited) can be password protected. There are no automatic links between a user's primary blog and secondary ones, including through the API. There is also no way to tell if a particular profile is primary or secondary, or the account to which a secondary blog is attached. Secondary blog owners may also grant write access to other system users, enabling multi-user profiles. Blocking users prevents the blocked user from interacting with or seeing content.

How can profiles be exported from or imported into a system?

In the Indieweb model of profile ownership, all data is assumed to be on a server controlled, or at least trusted, by the profile owner. As such, they can move it however they please. Similarly, Pump.io and Friendica are open source software platforms which allow people to either opt to use an instance on a server they trust, or install their own instance for complete control. They both use the standard ActivityStreams 1.0 data model [as1] (Friendica has extensions); while Friendica provides import/export functionality in the UI, Pump.io doesn't, however the database or JSON feed is compatible across instances.

Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, LinkedIn, ResearchGate, and RunKeeper provide a download link for an archive of content. In most cases these are a snapshot of current profile attributes, without a history of changes, except for Facebook, which provides a comprehensive activity log. All exports are proprietary schema in JSON, HTML or CSV.

StackOverflow profiles are reusable across different StackExchange sites; there is no export, however there are public dumps of Q&A data. GitHub data is available through an API.

Tumblr, CouchSurfing, Quora, OkCupid, PeoplePerHour, AirBnB and Zooniverse provide neither an export nor an API to access all profile data.

What constraints are placed on a profile?

In this section I examine the terms of service of systems to determine how users are expected to engage. In some cases these are enforced by technical constraints.

Twitter, CouchSurfing, Facebook, OkCupid, LinkedIn, PeoplePerHour, AirBnB and GitHub state that a user may not have multiple accounts. Twitter qualifies this with "overlapping use cases".

Tumblr users cannot create two primary blogs with the same email address, and can create 10 secondary blogs per day on the same login with no overall limit. Secondary blogs are somewhat constrained in their functionality compared to primary blogs.

Couchsuring, Facebook, Quora, StackOverflow, LinkedIn, PeoplePerHour, AirBnB, GitHub and RunKeeper explicitly disallow 'fake' profiles; the profile owner must be a single 'real' person, and not be impersonating someone else.

What is the data model of a profile?

To answer this question, I have examined wording in systems' documentation around profiles, in user interfaces as well as APIs. Where possible, I have also looked at internal data models of the software.

Accounts and people are roughly equivalent for Twitter, Indieweb, Pump.io, LinkedIn, Facebook, Quora, PeoplePerHour, ResearchGate, OkCupid, AirBnB, Zooniverse, RunKeeper, and GitHub profiles. That is, a profile sufficiently identifies a person; for example the "name" attribute of a profile is the name of the profile owner (rather than the name of the profile). Activities associated with these profiles (e.g. "distance ran" or "commit made") are assumed to have been carried out by the profile owner.

Tumblr and YouTube equate an account - or username/password combination - with a person, but each account may be attached to multiple profiles: secondary blogs in the case of Tumblr, channels in the case of YouTube. Profile owners can carry out interactions from behind one of these profiles at a time.

Friendica permits a user of one account to create multiple profiles with different attributes, and set up access control so that certain people see a particular profile. Different profiles are different 'views' on one person. Profile owners can also assign a 'type' to their profile which automatically sets some defaults for privacy and access control settings.

What is the profile for?

This question looks at the purpose of the profile within the system, rather than any purpose of the system itself, though the two may be similar.

In Twitter, Tumblr, YouTube, Quora, StackOverflow, Indieweb, ResearchGate, Zooniverse, RunKeeper and Github, profiles serve as a central hub for aggregation of content by the profile owner. In the cases of Twitter, Tumblr, Pump.io, CouchSurfing, Facebook, LinkedIn and Friendica, a profile serves as an endpoint for connections and relationships within networks where connections are important.

In systems with high levels of interaction and often some concern about trust or reputation, profiles provide a face behind content so that statements may be evaluated against the backdrop of 'who said it' (e.g. Twitter, Tumblr, Pump.io, YouTube, CouchSurfing, Facebook, Quora, StackOverflow, ResearchGate, Friendica, Github). Systems which are particularly geared towards building trust or reputation as a foundation for future relationships and interactions within the system are CouchSurfing, Quora, AirBnB, OkCupid, StackOverflow, LinkedIn, PeoplePerHour, ResearchGate and Zooniverse.

Profiles which are geared particularly towards self-expression, or establishing a presence, are Indieweb, Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, Pump.io, YouTube and Friendica.

Who is the profile for?

Often who a profile is intended for is related to the profile's purpose within the system. In some cases, the audience is known (e.g. you know who follows you on Twitter; Tumblr, Pump.io, YouTube, Facebook, Quora, LinkedIn, Friendica, RunKeeper, Github) and in other cases imagined (you have an idea of who OkCupid might be promoting your profile too, but no sure evidence; the same for CouchSurfing, StackOverflow, Indieweb, PeoplePerHour, ResearchGate, Zooniverse) and in some cases both (your Twitter profile is public, so people who aren't your followers will see it; also similar for Tumblr, Pump.io, Facebook, Quora, LinkedIn, Friendica, RunKeeper, Github).

In cases where a profile is constituted of an aggregation of personal data, content, and online interactions, the profile owner is a member of the audience, as they can use it for self-reflection or self-expression (Twitter, Tumblr, Pump.io, YouTube, Facebook, Quora, OkCupid, Indieweb, StackOverflow, LinkedIn, ResearchGate, Friendica, RunKeeper, Github).

Systems like Quora, CouchSurfing, OkCupid, StackOverflow, LinkedIn, PeoplePerHour, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and AirBnb use data from user profiles as input to core algorithms which enable the system to function, providing a service to profile owners.

Similarly, systems such as Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, YouTube, CouchSurfing, LinkedIn and RunKeeper use profiles as input to algorithms which sustain the companies behind the systems, for example through selling data to third-parties like advertisers.

Features

From this analysis, five features of profiles were derived and are described below, and summarised in Table 3.

| Feature | Strongly applies (1) | Does not apply (0) |

|---|---|---|

| Flexibility | Profile owners have choice about the kinds of content associated with their profile and how it is presented. | Profiles are generated as a side effect of owner's activities or automatically (e.g. from sensor data) and owners cannot amend. |

| Access control | Profile owners have control over which parts of the profile others see. | Profile owners have no control over what others see. |

| Prominence | Profiles are integral to functioning of the system as a whole. | Profiles are a side-effect of some other function of the system, and/or not necessary to use the system. |

| Portability | Profile owners can move their data in or out of a system. | Profile data cannot be imported or exported. |

| Representation | The profile is a person, as far as the system is concerned. | The profile is a document describing some aspect of a person(a). |

Flexibility is a function of the different types of content/data which make up a profile, and the relationship the profile owner has with those who see or use their profile. As some times of content are under more control of the profile owner than others, we consider the proportion to which they make up the profile, and weighting given to each. Flexibility also considers the systems technical or policy constraints around profile contents.

Access control involves the granularity of the controls, the extent to which profile owners can opt into or out of publishing certain aspects, and the awareness of the owner of who their audience is.

Prominence takes into account the extent to which a system would function were users' data (of the various kinds) not aggregated into profiles. Prominence of profiles may depend on the role a user is playing in the system, so the potential varying roles are also taken into account. Systems with a high emphasis on connecting people feature profiles prominently, whilst systems with lots of interactions but little need for reputation do not necessarily require consistent profiles to be useful.

Portability considers how easy it is to get profile data out of a system, as well as how reusable that data is in other systems. This includes whether data is exported into a known standard data model, and standard file format, and the extent of additional processing that may be required to port it elsewhere.

Representation connects the systems' model of users with its purpose. Systems with the possibility or expectation of personas or partial representations of individuals are not considered representative, whilst systems with emphasis on 'real people' and one-to-one mappings between profiles and profile owners have high representation. Systems in which the real-life human is required for legal or transactional purposes (e.g. to make a payment or provide a service) make a distinction between the profile and the person, and this lowers representation.

An overview of the questions which contributed to the derivation of each feature is in this table and the rankings of each system against each feature are in the following table.

| Feature | Questions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| Flexibility | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Access Control | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Prominence | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Portability | X | X | ||||||||

| Representation | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| System | Flexibility | Access Control | Prominence | Portability | Representation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AirBnB | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| CouchSurfing | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | |

| Friendica | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.2 |

| Github | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| Indieweb wiki | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.9 | |

| OkCupid | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| PeoplePerHour | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| Pump.io | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Quora | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| ResearchGate | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| RunKeeper | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| StackOverflow | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| Tumblr | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| YouTube | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Zooniverse | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.8 |

Discussion

Five features of online profiles were derived from observations of the functionality and uses of a set of existing social systems. We can use these features to cluster similar systems and give us a better understanding of online profiles in the social web ecosystem today. In this section I discuss some noticeable clusters. When I use 'highly' in reference to a score, I mean the score was greater than 0.5.

Though much of the literature around studying user profiles only acknowledges attributes [dcent, counts09] we can see that profiles are constituted of much more than just descriptive attributes about an individual. Content that makes up a person's profile may be input directly by the profile owner, generated or inferred from their online or offline activities, combined with content of others in the system and/or generated directly by other users of the system. Different systems emphasise different aspects of a person's online presence and allow users to adjust this to varying degrees.

The features which enable greatest control over self-representation for users are flexibility, portability and access control. Flexibility means that users have freedom to choose which information and contents make up their profile; portability means that they can move this data around or repurpose it easily; and access control means that the profile owner can choose who sees what. These things in combination are particularly empowering. Thus, the systems which give users the greatest control are Friendica and YouTube, which score highly for all three, and Tumblr, which scores highly for flexibility and access control. To a lesser degree, Pump.io, Indieweb and ResearchGate score highly for flexibility and portability, but with limited access control. This means that profile owners must employ strategies of omission or self-censorship to effectively manage what their audience sees. Facebook and LinkedIn on the other hand score very highly for access control, but lower for flexibility and portability; that is, you don't have much control over how your profile is constructed, but at least you can control who sees the information.

Systems with high prominence scores tend to also have high representation scores. However Friendica has a very high score for prominence, as profiles are crucial in a network where making connections is the end goal, but it has a low score for representation, as the expectation is that profile owners present personas, and may have more than one for different aspects of themselves. The high-prominence and high-representation systems (CouchSurfing, PeoplePerHour, AirBnB, OkCupid, Facebook, LinkedIn) have strong ties to 'real life', for example in-person meetings, employment, or service exchange.

Low prominence systems are geared towards an end purpose that is not oriented around user profiles, such as content creation, collaborative projects or information aggregation (Zooniverse, YouTube, Twitter, Quora, StackOverflow, ResearchGate, Github, Tumblr, RunKeeper). Profiles are useful, but not an end in themselves. On top of being low prominence, Tumblr and RunKeeper are not very representative; Tumblr permits multiple profiles and the community generally expects anonymity or pseudonymity; RunKeeper contains a very small subset of information about a person. Zooniverse, StackOverflow, Quora and Github nonetheless score relatively highly for representation, since unique profiles for individuals is necessary for establishing reputation or standing, a key element in these communities.

To be able to classify systems according to these features it is necessary to consider multiple perspectives: those of the profile owner, others who will see the profile, and the organisation which runs the system itself. As such, the classification process gives a holistic view of a system, but only at a surface level. It misses out on the finer details of how the system is situated in the context of a society, how profile owners use one system alongside others, and the multiple possible uses of a system by different people, or different roles people may play. Nonetheless this provides a baseline idea of how people could use a system, in order to carry out more detailed studies about how individuals actually do use a system.

In particular, in future studies of users of a particular system, researchers can refer back to the features of the system (perhaps scoring systems which have not been covered here, or updating scores for ones which have changed) in order to put the users' actions in the bigger picture.

Throughout the remaining studies in this chapter, where specific systems are highlighted, I refer back to these features.

Contributions to the 5Cs

Different systems require different levels of engagement with one's own profile. The prominence of a profile within a system, as well as how representative a profile is (or should be according to system rules) of its owner indicate that individuals may have different levels of control over their self-presentation. Relatedly, if one can take all of one's data out of a system and even move it elsewhere (portability), this may influence decisions about persisting or maintaining profiles.

Systems may be flexible about what data appears in a profile, how that data is presented, and how it is accessed by other users. I consider both of these features to contribute towards the customisability of self-presentation.

Access control and flexibility both indicate an awareness of the profile owner's audience. These, along with the prominence of a profile within a system, indicate that we must pay attention to the links between participants within a system, or the connectivity.

Users of systems are affected by both technical and policy constraints in terms of flexibility and portability of their profiles. The purpose of the system itself also influences the prominence and representation of profiles. These outside constraints and goals constitute the context formed by a system, as well as being influenced by the overall context in which a system exists (eg. legal frameworks, business interests).

Representation and access control together can drive or inhibit linkability between profiles in different systems, and offline identities. The spread and aggregation of information about an individual, possibly without their knowledge or consent, is part of the cascade of information beyond where it originated.

Constructing online identity

In the previous study we took a high level look at 18 social systems; in this study, we zoom in on one of them — YouTube. According to the previous study, YouTube channels are relatively flexible, access controlled, and portable, but not very representative, and even less prominent. Users participate in different roles on YouTube, from passive, possibly anonymous consumption, to engaged consumption with comments, interactions and curating playlists, to active content creation. The latter group also vary the level to which they participate; some users spontaneously or casually post videos for a small localised audience; some engage across multiple channels, manage branding, collaborate, nurture a fanbase, and create videos on a professional level.

The high flexibility and low prominence of YouTube profiles gives users a chance to be creative when expressing their identities. The following study empirically examines some different ways identities are expressed through YouTube channels, including a closer look at the affordances of the system and how individuals work within and outside of these.

Whilst YouTube is at the core of the online presences of the subjects of this study, their activities span a variety of other systems, not wanting to fall into the trap of imagining a system exists in isolation, I discuss these as well.

I identify four concepts that are useful for understanding individuals in a system with flexible self-presentation opportunities: roles, attribution, accountability, traceability.

This section has been adapted from work published as Constructed Identity and Social Machines: A Case Study in Creative Media Production (2014, Proceedings of WWW, Seoul).

Introduction

In chapter 2 I described existing work in understanding socio-technical systems as social machines. Due to the complex nature of online identity, understanding nuanced identity behaviours of social machine participants in a more granular way is crucial. First I will briefly describe creative media production social machines, then present the results of a study of profiles portrayed by participants in one of these. The contribution is a set of dimensions along which a social machine can be classified in order to better understand human participants as individuals, as opposed to participants in aggregate.

Amongst the plethora of user-generated content on the web are a huge number of works of creative media, and behind these are independent content creators pushing their work to a global audience and actively seeking to further their reach. Within this ecosystem we can see creative media production social machines on a variety of different scales. The definition of creative media production social machines encompasses a class of systems where:

- humans may use a purely digital, or combination of digital and analogue methods, and a degree of creative effort, to produce media content;

- the content is published to be publicly accessible on the web;

- a global audience may consume, curate and comment on this content in technologically-mediated environments.

These social machines exist both within and across content host platforms (e.g. YouTube) and within and across online communities and social networks. Many, if not all, media types and genres are represented among the media artefacts that emerge from these systems, and the content and the reception it receives can have a sometimes profound effect on media and culture in the offline world.

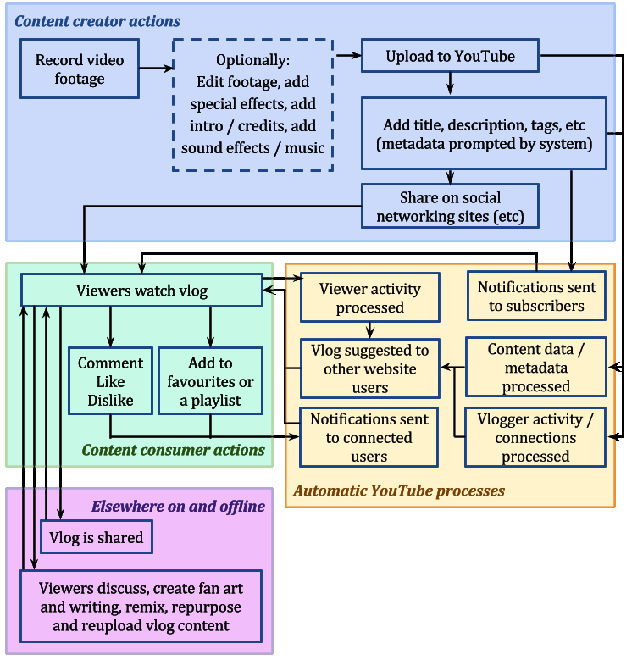

Figure 2 shows the interconnected social and technical systems engaged when a simple vlog (video blog) is uploaded to YouTube. These processes would be further expanded if the creator was to branch out and produce different types of content, collaborate with another creator, cross-publicise, share audiences or even co-own a YouTube channel or other website profile.

Creative media production social machines create an environment in which content creators of all backgrounds and abilities are able to publish outside the constraints of traditional media channels. These creators are actively vying for attention from massive audiences; competing for views, likes and shares on a global scale. How they present themselves to their audience can be critical to their success, but also a ground for playful experimentation.

Motivations for participation

It is worth noting that there are a variety of motivations or incentives for content creators to participate in creative media production social machines.

Some content host sites provide direct financial incentive for popularity (e.g. YouTube's Google Adsense). Others facilitate a commission based model, where creators show off their work and take paid requests for custom pieces from the community (e.g. DeviantArt). For content creators who publish primarily on such systems, their activity on other systems is usually tied to driving traffic back to the content which makes them money, or entertaining the fanbase from whom they thrive (e.g. a creator who publishes sketch comedy on YouTube might use their Twitter account to tell original jokes to maintain interest between video releases).

But for many content creators, the financial rewards from their chosen content host sites might be a convenient side-effect of doing something that they love. Reputation as a creator of high quality content, as a talented artist or as a particularly funny comedian might be their primary driver. There are also social cues in many communities that affect content creator behaviour. Sometimes creators don't want to be accused of 'pandering' to their audience or losing their artistic integrity, and regulate their behaviour accordingly.

The visibility of quantitative data collected by a content host site – such as how many views a piece of content has, how often a participant is referred to as a co-creator, or how often a participant responds to viewer comments – may also impact behaviour. Technical factors are often highly conflated with the social norms in a community.

Thus, the core reasons for creating content can affect both the content created and how creators present themselves to their audience in the process.

Context and research questions

To recap some background from chapter 2, the nature of identity and anonymity in online spaces is well discussed [Donath2002, Halpin2006, Rains2007, Ren2012]. Humans naturally adjust the way they present themselves according to the context, and different online spaces may afford different levels of flexibility in doing this. Systems which don't require any kind of registration to post content, allow people to adopt and discard personas as needed, and to create social cues to identify each other that are not designed as part of the system [Bernstein2011]. Entirely different behaviour occurs in systems that strongly encourage or even try to enforce usage of real names. Often it is trivial for people to create multiple accounts under different pseudonyms anyway, but there may be an increased expectation of honesty from other users of the system, which itself affects the culture of communities within.

In many cases the fact that people present themselves differently in different contexts is unconscious; a side effect of their participation in a particular system according to the social norms or even technical affordances (e.g. their desired username may be unavailable resulting in the forging of new branding around an alternative). In other cases, the creation of alternative personas is engineered and deliberate, either from the outset or as something that has evolved over time. Multiple individuals may also participate in the portrayal of a single persona [Dalton2013] and one individual may present versions of themselves through multiple personas.

The public profiles of content creators were examined with the following questions in mind:

- How do content creators present themselves within and across communities?

- To what extent are content creators' online presences consistent across platforms, and how is their content distributed across different online presences?

- How, and to what extent, do content creators present connections between their own online presences?

To add depth, I also take note of their audience, the type of content they create, and the capabilities of the platforms on which they publish their content.

Study design

This is an in-depth empirical study in which publicly visible data about individual social media users are analysed. The data includes content created by the subjects, attributes from their profiles, and links between profiles. We use only human-led, in-browser exploration of the profiles, and employ no scripts or API access to gather data.

Method

I first familiarised myself with the different ways of updating and modifying the data that appears on a YouTube profile (also known as a channel), so I could understand the actions that profile owners had to undertake to build their presence on YouTube.

The starting point for data collection was a particular YouTube channel per subject. The different types of profile information that were present were noted. Links from the profile content were gathered, and ones which were determined to connect to other profiles, within and outside of YouTube, were followed. The information on these profiles was similarly logged. I collected:

- The types of profile data visible.

- The number of inbound and outbound connections to other profiles.

- What kinds of other profiles belonging to the channel owner were linked to from a YouTube channel.

- How these links were labelled or described.

- How the data on these additional profiles differed from or overlapped with each other.

Subjects

Ten content creators were selected from a subset of creators with whose content I have a passing familiarity through encountering it online over prior months to years. This resulted in a broad spectrum of content types (video, animation, music, art, written word) genres (comedy, game commentaries, educational, political), popularity, well-knownness and activity levels. I deliberately examined content creator profiles from the perspective of a content consumer, or casual audience member. Thus, for the purposes of this study, we do not have access to deeper insight about the personas beyond what is accessible publicly through the web. To identify each subject for the remainder of this study I use short non-anonymised nicknames.

Limitations

The results are based upon a very small (albeit diverse) sample, and cannot be considered representative of content creators in general. I seek to describe a subset of behaviours within content creation social machines, but do not claim to be exhaustive.

I have no doubt that content creators have more online profiles which are not linked from their YouTube channels, however I was obviously not able to discover and study these.

Results

Profiles and personas

For ten content creators, 93 profiles were discovered. Of these, 23 were YouTube channels, 16 Twitter profiles, 13 Facebook, 9 Vimeo, 7 Tumblr, 6 personal websites, 5 Instagram and 4 Vine, 3 Google Plus, 2 Bandcamp and 2 DeviantArt and 1 each of Patreon, FormSpring, BlipTV, and Newgrounds. Table [6] shows how the profiles are distributed. As we can see, in the domain of creative content production identities are not site- or community-specific. Creators spread their activities across a number of networks in order to shape a more complete identity.

| Creator | # profiles | Mean profiles per site |

|---|---|---|

| Dane | 18 | 2.3 |

| Khyan | 13 | 1.9 |

| Bing | 13 | 1.3 |

| Lucas | 11 | 1.4 |

| Bown | 9 | 1.5 |

| Todd | 7 | 1.2 |

| Arin | 7 | 1.0 |

| Suzy | 6 | 1.2 |

| Ciaran | 5 | 1.3 |

| Chloe | 4 | 1.0 |

'Second channels' are common on YouTube. Creators who focus on one type of content (e.g. sketch comedy) publish this on their main channel as well as using their main channel identity for interactions on the site. On their second channel they publish content that they may consider to be of interest to only a part of their main audience, such as vlogs about their lives, out-takes from main channel content, or experimental pieces. Most content creators with second channels post explicit links to them on their main channel, and often publicise them within content metadata or as part of the content directly. In some cases, including those where the connection between two channels is explicit and obvious, the creators behave differently towards their audience through second channel content. This varies greatly depending on the type of content produced. In some cases, second channels may be perceived to be more reflective of the creator's 'true' personality, if they project themselves as more serious or honest, and publish more personal content like vlogs or behind-the-scenes footage. Whether or not this is accurate is impossible to know without intimate knowledge of the creators' offline life. The significance is that persona variations exist, and creators do not necessarily hide these alternative presentations of themselves from their audience.

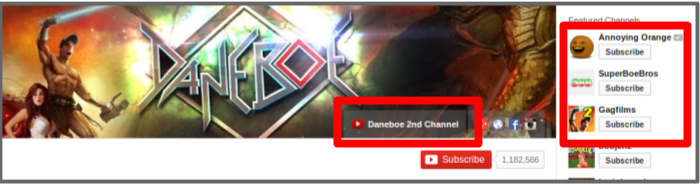

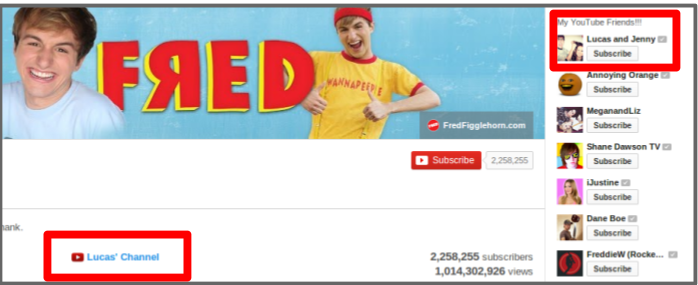

Additionally, there are profiles which are not directly linked from the (self-identified) 'main' profile, or the links are treated as though the profile belongs to a different person. Figure 3 shows three screenshots of different YouTube channels showing different ways creators link out to other versions of themselves.

Creators also used their profiles to link to shared channels (where either multiple creators post content independently of each other, or creators collaborate to produce joint content, or a both), and channels of others with whom they regularly work.

Most of the platforms discovered which host profiles for the subjects of this study offer limited options for customisation, and the use of consistent branding between different systems was intermittent. This mostly took the form of identical or similarly styled display pictures, similarly phrased introductory paragraphs, and similarly styled content.

Some creators have profile sets across different platforms which are distinctly grouped into alternative personas. This was evident from the branding, content and connections between them.

Connections

How connections to other people were represented varied depending on the technical system. We can differentiate between mutual relationships between accounts (e.g. 'friend') and one-directional relationships (e.g. 'follower', 'subscriber'). Some systems offer both types of relationship, some one or the other. For YouTube channels, popularity ranged from over 3.5 million subscribers for Dane's character channel realannoyingorange to 118 for Bown's secondary bowntalks channel.

The importance of these connections varies depending on the system as well as on the attitude of the system user. Mutual connections may initially be presumed to indicate a closer relationship, but this is not always the case. Some systems allow users to accept all friend requests en masse, which they may do to please fans, resulting in a lot of essentially meaningless mutual connections. Instead, outbound one-directional connections come in far smaller numbers, and indicate the content creator is particularly interested in the outputs of the other creators they choose to follow. It appears normal for content creators to follow other creators with whom they have collaborated.

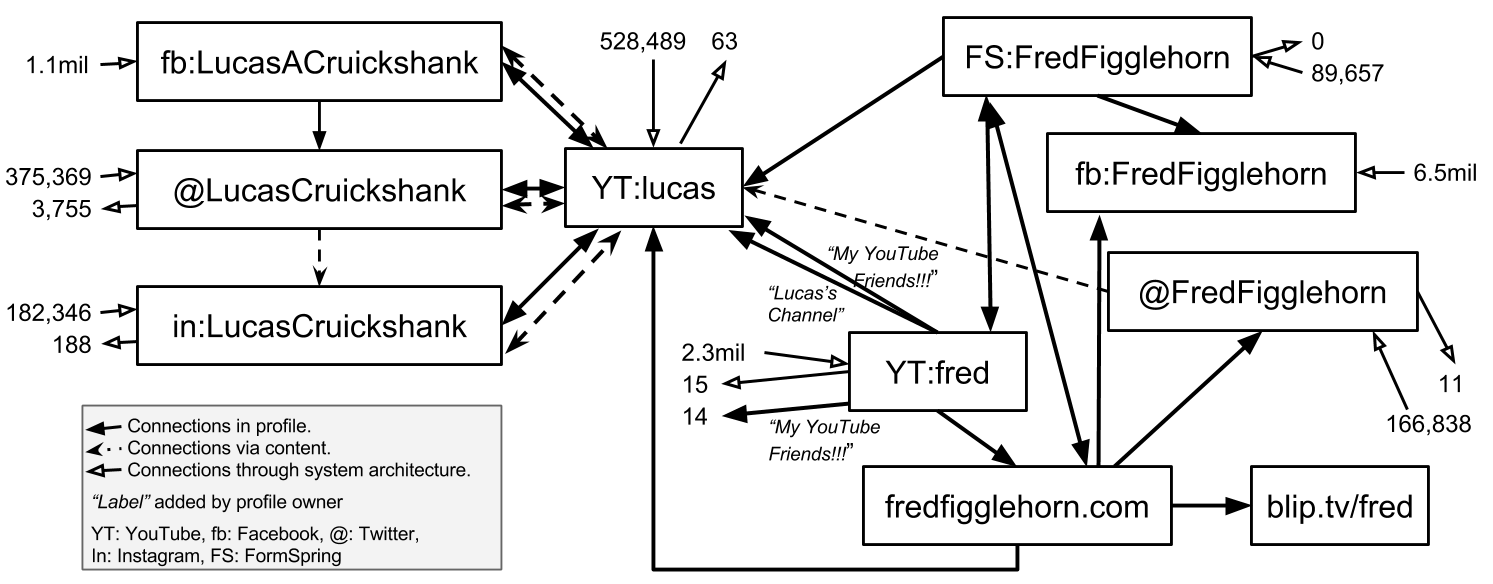

Although their use is to some degree shaped by community norms, such connections are strongly influenced by the architecture of the particular website. However, most of the websites examined allow enough control over the textual content of a profile that profile owners can manually create links to other documents on the web, potentially circumventing the site's built-in connection mechanisms. Creators may also be able to adapt the content publishing interfaces to add additional connections (e.g. adding links to Twitter and Facebook accounts in the description of a YouTube video), and often do. These connections necessitate extra effort on the part of the content creator, and tell us more about their relationships with other online accounts. Figure 4 shows different types of connections between profiles and personas for one content creator.

Summary

Content creators at all levels of activity do not have straightforward relationships with the systems they use for publishing and publicising their content. Through manually examining profiles, it is possible to identify personas, and connections between creators, and learn about the likely explanations behind them. Currently there is no way to formalise these deductions, so in the next section I propose a small taxonomy for describing the experiences of individual participants in social machines.

Taxonomy

Based on the findings previously described, I propose four closely linked but distinct concepts that are useful in a granular discussion of identities of social machine participants: roles, attribution, accountability and traceability. I will explain each in the context of creative media production social machines, and show how they can be used as dimensions to assess the nature of individual identity in a social machine.

| Dimension | Description | Degree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.5 | 1 | ||

| Roles | the ease with which participants can change the role they play in a system | one role, everyone equal | multiple roles, participants play one | multiple roles, participants move between them |

| Attribution | whether or not crediting participant contributions is important | unimportant | sometimes important | very important |

| Accountability | whether the provenance of the inputs make a difference. In a Social Machine where this is critical, regulating identities to ensure trustworthy data would make sense | unimportant | sometimes important | very important |

| Traceability | the transparency or discoverability of connections between different profiles and personas | required, or mostly useful | optional, may be useful or harmful | not required, or likely harmful |

Roles

A creative media production social machine contains at least consumers, commentators, curators, and creators [Luther2007a]. These roles are interchangeable, and content creators may wish to adopt different personas according to the role they are playing. Plus, content creators are often multi-talented and they may wish to put on a different face according to the different types of content they publish. How easily this is accomplished - according to the social expectations and technical affordances of systems that are part of a social machine - can impact the behaviour of participants.

Attribution

In content creation communities, contributions to media output are directly connected to building reputation, so content creators generally desire to have their name attached to work they produce. If the publication system does not allow this directly, as is often the case for sites that host collaborative works (a video published on one YouTube channel may contain contributions from several creators, each with their own channels but formally linked with only the uploader), then creators adapt the system as best they can, eg. the uploader may list links to the channels of all contributors in the video description [Luther2010]. Even when a content host site provides automatic linking to other user profiles – common in remixing communities – this isn't necessarily enough. [Monroy-Hernandez2011] finds that human-given credit means more, and so free-text fields for content metadata are often used anyway.

Accountability

In many of the commonly-discussed social machines, like Wikipedia, Galaxy Zoo, Ushahidi, and the theoretical crime data social machine in [ByrneEvans2013], accurate data is critical to the usefulness of the output of the system(s). Thus, accountability through identity is important. It is reasonable then to want to regulate participants somehow. But this is not universally applicable.

The production of creative content is a domain that exemplifies the need for taking a more flexible approach to identity understanding and management. On the one hand, creators wish to be accurately credited for their work and plagiarism may even result in a financial or reputational loss. On the other hand, creators may appear under multiple guises, engage in diverse behaviours and make contradictory statements about their participation in a creative work, all in the name of entertainment. Creators may also engage in some activities under an alternative identity in order to avoid any effect on the reputation of their main persona. These are valid uses of the anonymity provided by online spaces – a core feature of the World Wide Web. These activities won't necessarily even result in diminished trust. A content consumer may fully enjoy a series of vlogs, unaware that the vlogger is a character and the life events portrayed are entirely fictional, and be none the worse off for it.

Traceability

We consider traceability in terms of the settings in which an individual might interact with others. A person participating in a creative media production social machine may exist behind a different persona when participating in a scientific discovery social machine, and yet another in a health and well-being social machine. The discovery that other participants in the health and well-being social machine are aware of their alternate persona in the creative media production social machine may cause them to amend one or both of their personas. If the risk of their multiple identities being 'discovered' is high they may adjust their behaviour accordingly, whether this is ceasing all attempts at 'deception', or taking steps to decrease the overlap of the communities of which they are a part.

Well known content creators often appear at offline events to meet their fans. Those who star in popular live-action video content are recognised in the street. They are interviewed by journalists and contracted to produce viral adverts by marketing companies. Only with careful control of their online persona can they successfully engage in offline interactions like this. A content creator who believably portrays an undesirable character across multiple platforms online may not be considered a candidate for a job in broadcast media thanks to the blurred lines between reality and fiction, online and offline.

In 2017, video game commentator Felix Kjellberg (PewDiePie) lost a lucrative contract with Disney and Google for using racist language in his voiceoversp. In 2014 vlogger Alex Day was widely renounced by his online community (as well as his record label) because of offline allegations of sexual assult and abusive relationships with fansa. Different worlds interact; contexts collapse, and the repercussions are felt through them all.

An example in which the traceability of personas was crucial is the DARPA Network Challenge [Tang2011], for which participants needed to provide their 'real life' identities to win the cash prizes. Even if they had operated under pseudonyms during the competition, in order to validate their claims they needed to make known these personas and consolidate them with an identity that would allow them to receive the prize money.

Since a YouTube profile is not assumed to be representative of a single complete individual, profile owners must find other ways to establish and moderate the relationships between their profiles. How they do this will depend on the roles they play, and their motivations in taking part. Knowledge of others present - audience and colleagues - in the online and offline spaces in which someone spends time may influence how they establish their personas in these spaces. An evolution of these spaces or a change in the individual's circumstances over time may cause them to revise their personas.

Applying the taxonomy

We can apply these concepts to social machines in order to understand the significance of individuals' identities within them. We use some well known social machines as examples for each dimension, in Table 8.

| Dimension | Examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Roles | ReCAPTCHA | The Obama campaign | Creative media production |

| Attribution | ReCAPTCHA | Wikipedia | Creative media production |

| Accountability | GalaxyZoo | Creative media production | A crime reporting social machine |

| Traceability | DARPA network challenge | Creative media production | Mental health support forum |

| Refer to Table 7 for descriptions of each dimension, and what the numbers mean for each dimension. | |||

Discussion

I have demonstrated through an empirical study that participants in social machines often have complex relationships with their own self-representation, and with their connections to others in a system. Individuals may have one-to-many or many-to-one relationships with online personas, for a number of different reasons, and with different levels of transparency. This section includes a taxonomy of four dimensions: roles, attribution, accountability and traceability. We can use these to better understand individuals in a social machine in relation to the whole, despite this complexity.

Contributions to the 5Cs

The role(s) taken on by an individual are affected by the extent to which an one is able to create and discard identities. Whether participants can be attributed or held accountable for their contributions, and the extent to which one identity can be traced to another, are affected by whether identities are persistent, and whether anonymous contributions are accepted. These are all aspects of the control someone has over their online self-presentation.

Roles arise through, and may be enforced by, either the technical affordances of a system, or the social expectations of a community (or both). The role(s) an individual chooses to take on may also be affected by their personal motivations, desires or needs. Thus understanding roles requires us to account for the context in which a system is being used.

Through Attribution and traceability we discover the connectivity of a system. Participants may see each others' contributions, and may build reputation accordingly and present a particular impression to their audience. This reputation and impression can translate to other technically disconnected systems if identities are transparently linked.

The degree to which connections between identities are traceable affects the spread of information about an individual. Intended or unwitting links between personas contribute towards an automatically generated or inferred aggregate profile. This spread may feed into unknown systems on and offline, and have unforseen consequences. I label this the cascade.

Deliberate traceability may be created between profiles on different systems through consistent visual branding, as well as actual hyperlinks placed in profiles and annotated. This is only possible to the extent that systems permit participants to customise their profiles.

The many dimensions of lying online

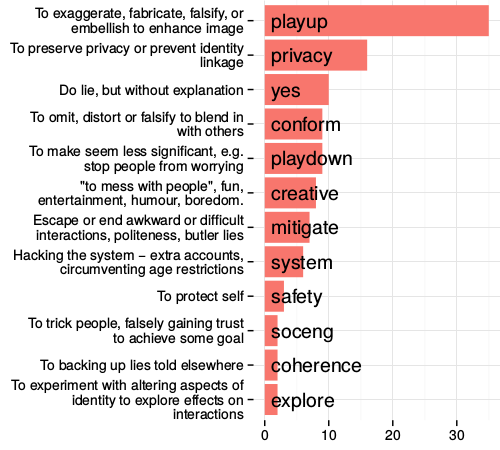

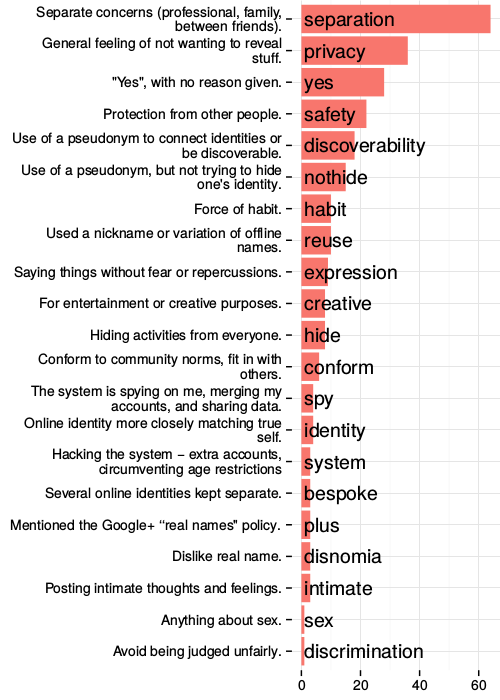

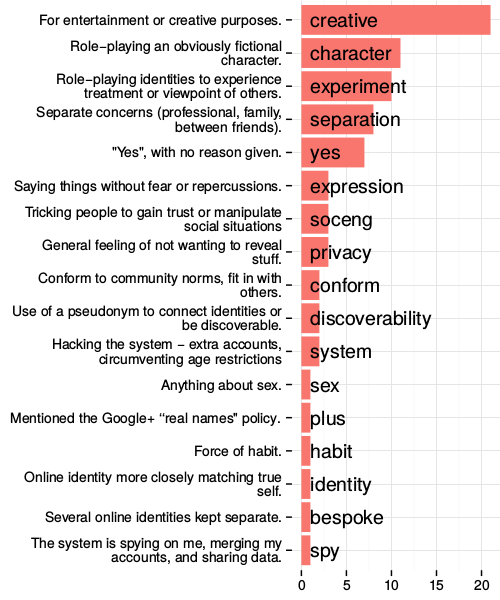

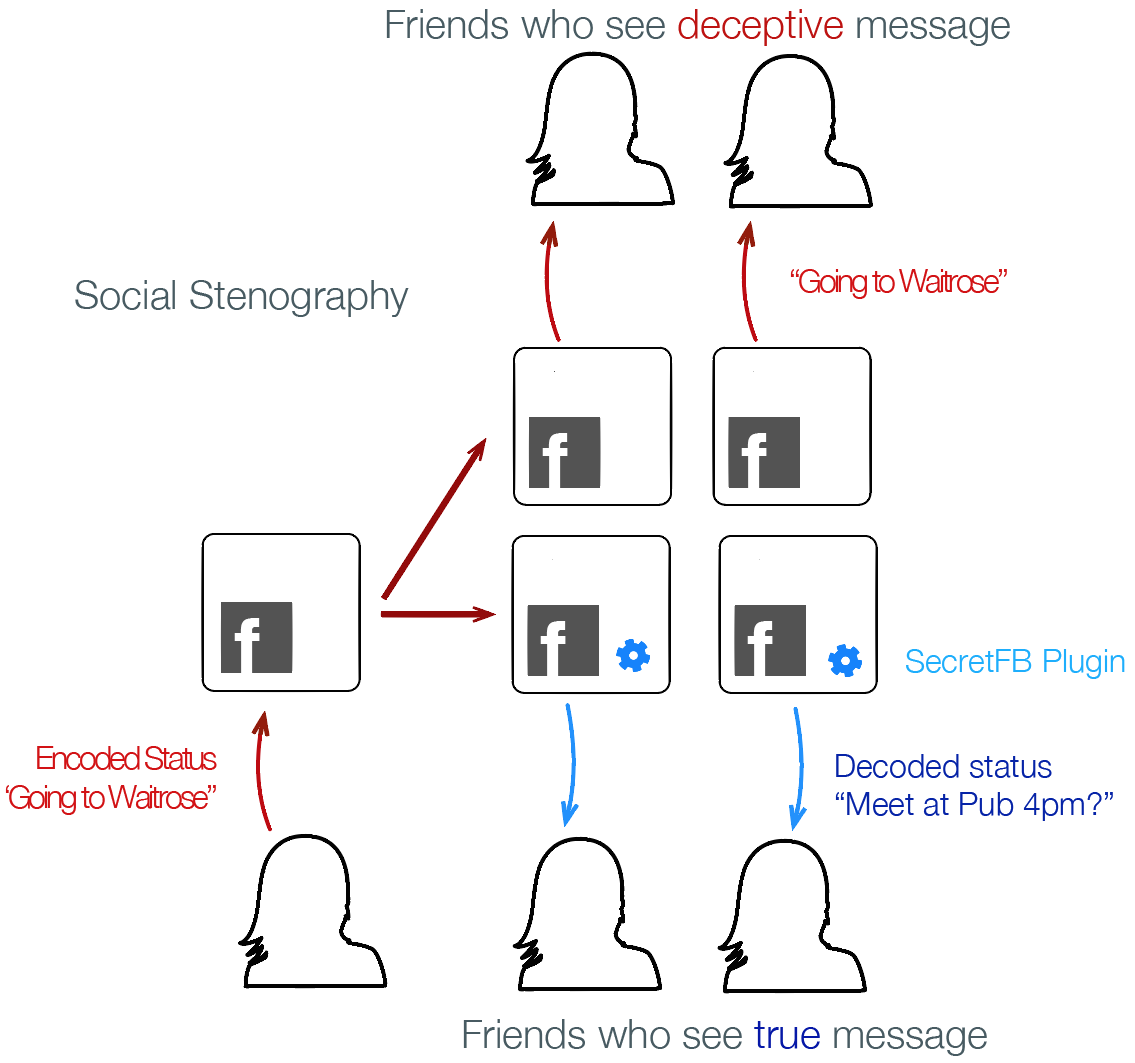

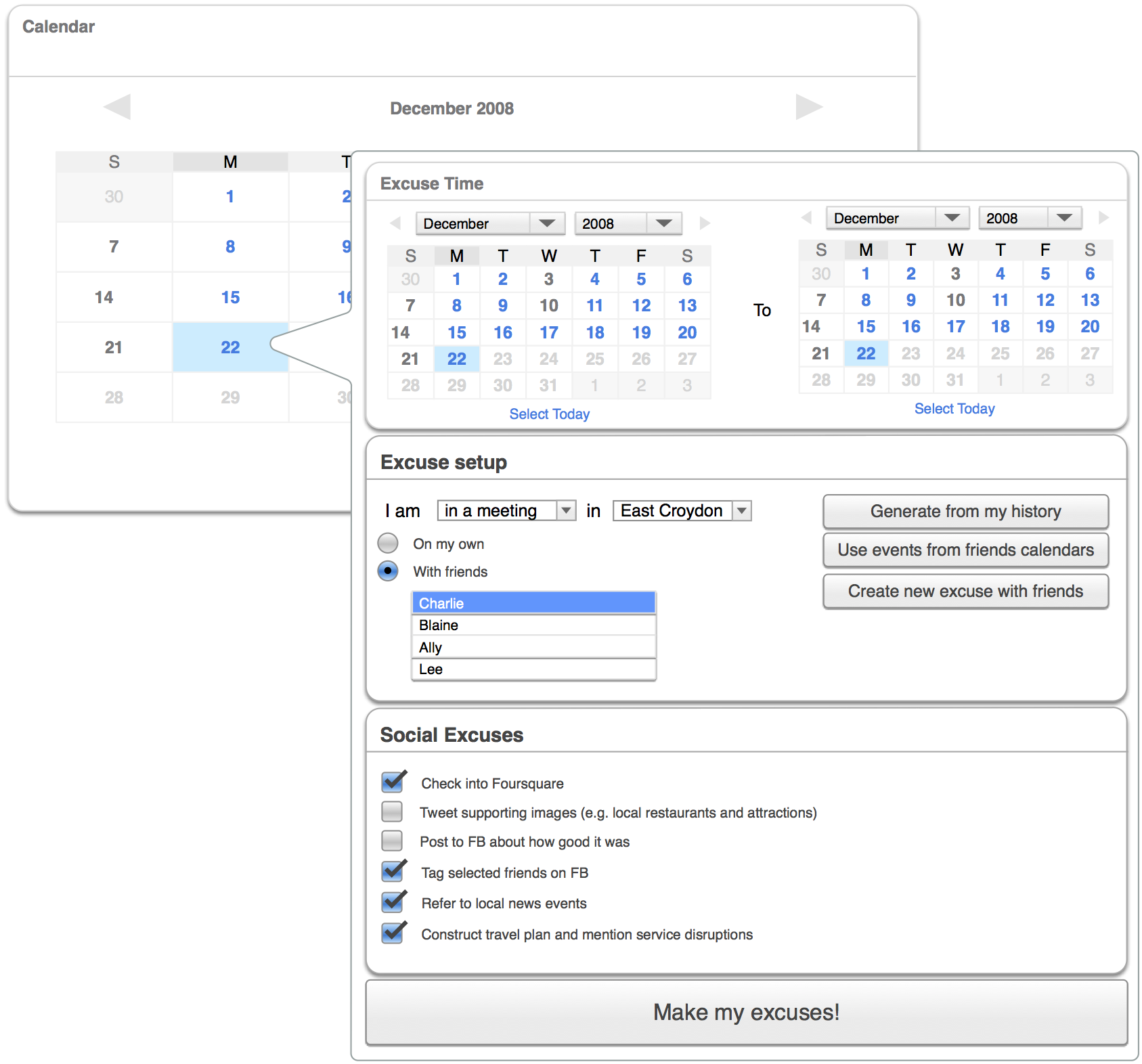

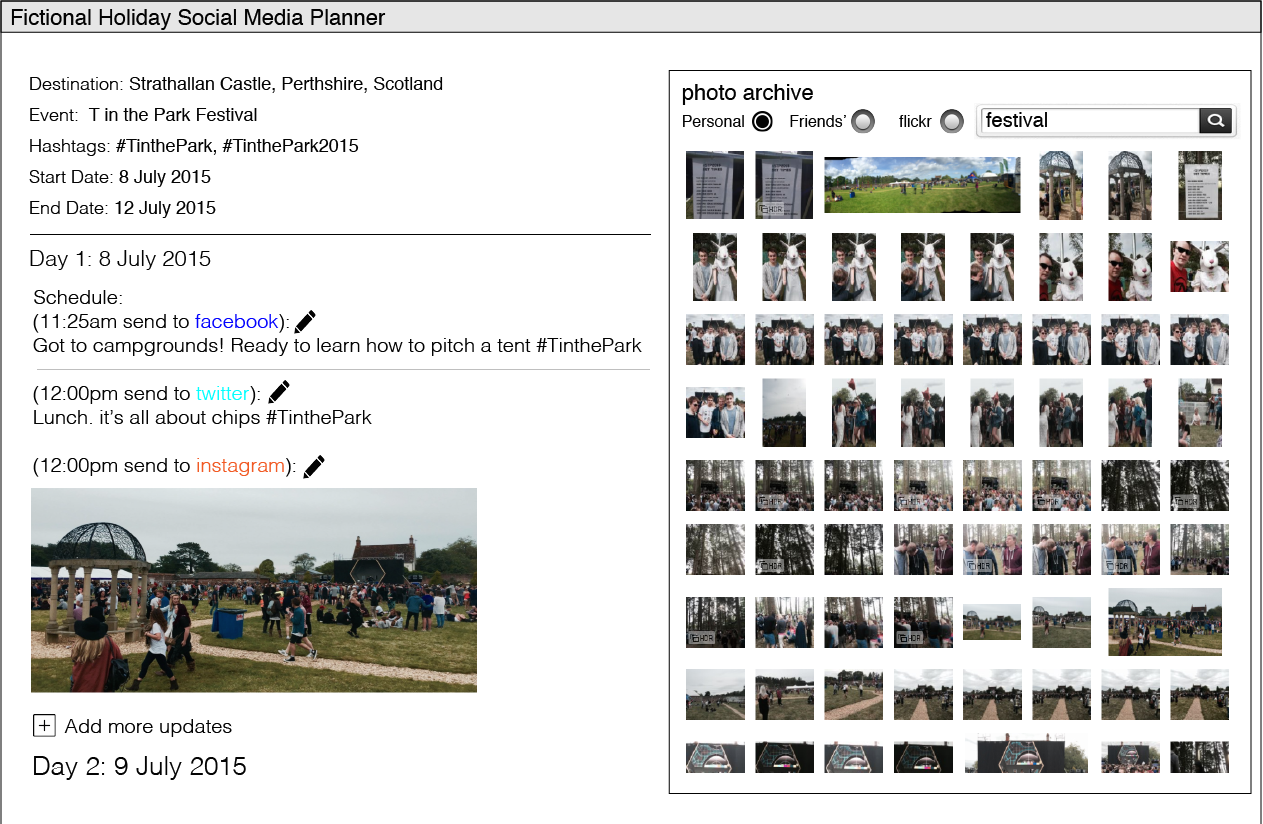

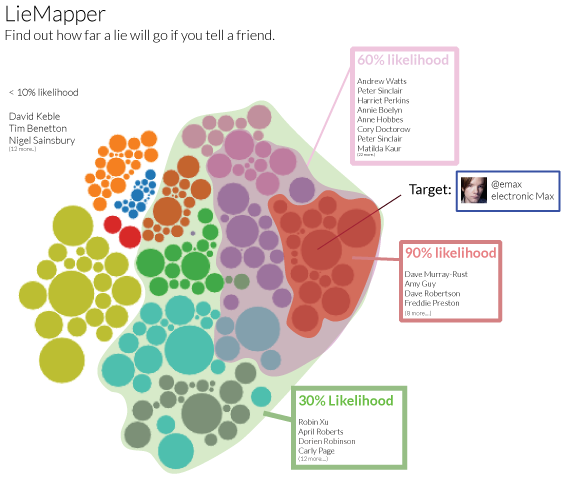

In the previous study we see some of the creative ways in which individuals work around constraints of even flexible profiles in order to meet their expressive needs. We learned that misrepresenting one's real-life identity is not necessarily in conflict with the functioning of the system, and may even be a culturally important aspect of participation.